Promises, Promises

A short and sweet introduction to JavaScript promises and how they’re used in the Web Bluetooth API

If you’ve not already seen, I’ve been making some fun things with Web Bluetooth recently. While I was getting to grips with this technology, I learnt that the ‘request device’ method, the one that allows your browser to connect to a remote device, returns a Promise. But what is a Promise? The spec says:

“The Promise object represents the eventual completion (or failure) of an asynchronous operation, and its resulting value.”

Ok great, but wait, what’s an asynchronous operation?! Uuuuuurrrrrgh!

Synchronous vs Asynchronous

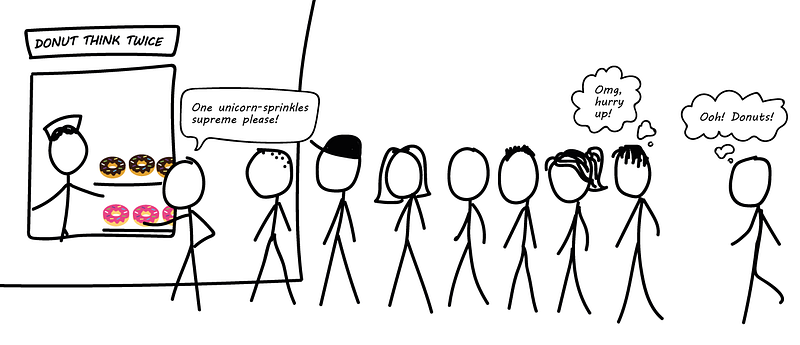

Imagine you’re at a new, trendy, hole in the wall donut vending shop. So is everyone else in the neighbourhood. You have to queue up to buy your NutellaFilledRainbowSprinklesUnicornSupreme and you won’t be able to get it til everyone in the queue in front of you has bought their donuts.

A queue at a donut shop

This is how synchronous code works. The lines of code are the queue, and they won’t execute until the previous one has finished.

Now imagine if instead of the hole in the wall, this enterprising donut vendor decided to open a donut restaurant. You can sit down, give your order to a member of staff and you can await you order’s arrival. You don’t have to wait for everyone else in the restaurant to order and receive their donuts before you can order.

A gif of a potential donut ordering scenario

This is how a little like how JavaScript can work asynchronously. When you call a function in JavaScript, it is like giving your order to the waitstaff. The function you called is not executed immediately. As much as you might like it to, your donut won’t just appear suddenly on your table. The call creates a message, which is added to a message queue. This is your order. It might have many constituent parts, a drink, multiple donuts etc. These constituent parts of the message are the function arguments and variables that will need execution. An ‘event-loop’ moves the messages to a ‘call stack’. That’s your waitperson taking your order to the kitchen. Once the call stack is empty of previous messages, then your message can be processed. The waiter will take the previous order from the kitchen and there will be space for the chef to start getting your dishes lined up and ready to take. The call stack will wait until all of the corresponding frames of your message are executed before your message itself is de-queued and your donuts are brought to your table.

A gif representation of the event

Promises

Ok, so that’s asynchronous behavior in a (do)nutshell. So what’s a promise?

When the waitstaff take your order they’re essentially promising to bring you a donut. You hope that they will bring you a donut, but many different things might happen in the time between your ordering said donut and the time for your order to ‘resolve’. When your order is made, the waitperson’s promise is in a pending state, it has been neither fulfilled nor rejected. When you can take your first delicious bite of donut then the waitperson’s promise has been fulfilled. But what if your waitperson drops it before getting it to you? They’d have reneged on their promise of a donut and in this case the promise would become ‘rejected’. Once the promise has been fulfilled or rejected then it becomes ‘settled’.

If we were to try and write this in Javascript it might look like this

const getDonut = new Promise(

(resolve, reject) => {

// Promise is pending, we can do other things

// while we wait for our donut to arrive.

if(/* unicorn sprinkles donut is in stock */) {

resolve("Here's your magical donut!"); // promise is resolved

} else {

reject(

Error("Oh no, we're all outta that flavour")

); // promise is rejected

} } );

getDonut.then((result) => {

// if we’ve got our donut console log the result

console.log(result);

}, (err) => {

// if we didn’t get our donut, console log what went wrong

console.log(err);

});

The promise constructor takes one argument, a callback function. This callback takes two parameters, resolve and reject. Inside the callback we can do other things if we need to. If the case that we’re testing against works then we’ll call the resolve method and if there is a problem we’ll call the reject method.

Promises will always return a value, which means that we can use the .then() method to react to the results of the promise. .then() takes two arguments, a success case callback and a failure case callback. We can respond to these two states appropriately within the bodies of the two callbacks.

Putting it to use — From sweet tooth to Bluetooth!

With this new understanding of promises lets take a look at what is happening when we connect to a device with Web Bluetooth.

The Web Bluetooth API gives us the navigator.bluetooth.requestDevice() method. When this line of code is executed (usually on a button click), your browser will show a pairing menu so that your user can pick a device to pair with. When the user selects a device by clicking on a menu option, the promise will become resolved, returning the device which has been paired as an object called bluetoothDevice.

We can use the .then() method to start interfacing with the this device, for example if we wanted to return the name of the device, we could return the name property.

The bluetoothDevice object contains more objects which contain information about how we can interact with the device, called services. It is possible to chain .then() methods in order to get access to these services, once the first promise has returned. In order to get the battery level of a device, for example, our promises might look like this

function onButtonClick() {

console.log(‘Requesting Bluetooth Device…’);

navigator.bluetooth.requestDevice(

{filters: [{services: [‘battery_service’]}]})

.then(device => {

console.log(‘Connecting to GATT Server…’);

return device.gatt.connect();

})

.then(server => {

console.log(‘Getting Battery Service…’);

return server.getPrimaryService(‘battery_service’);

})

.then(service => {

console.log(‘Getting Battery Level Characteristic…’);

return service.getCharacteristic(‘battery_level’);

})

.then(characteristic => {

console.log(‘Reading Battery Level…’);

return characteristic.readValue();

})

.then(value => {

let batteryLevel = value.getUint8(0);

console.log(‘Battery Level is ‘ + batteryLevel + ‘%’);

})

.catch(error => {

log(‘Something went wrong: ‘ + error);

});

I hope this short and sweet introduction to promises will help with your understanding of the Web Bluetooth API. If you’re making things using Web Bluetooth I’d love to see them! Tell me about your projects below or @thisisjofrank on twitter!

Tagged in JavaScript, Promises, Web Bluetooth, Introduction, Asynchronous

By Jo Franchetti on March 21, 2018.