Web Workers in the Real World

Comlink simplifies using web workers and makes them safer to use but beware these hidden costs.

I wrote this article whilst building a demo website which uses both expensive physics and an expensive SVG filter. It was important that it felt really tactile on mobile devices, so it had to run very smoothly.

Running both the physics and the SVG filter in the same thread was too expensive so I moved the physics into a Web Worker to take advantage of the available resources.

Using Web Workers can be very daunting especially if you are not familiar with parallel programming. The library Comlink helps simplify working wiht Workers. Here I discuss the benefits and drawbacks of working with Web Workers and how to optimise them for performance.

A brief history of asynchronous scripting in the JavaScript

The web has traditionally been single threaded. Each command would execute one by one waiting for the previous one to finish. In the early days even long running commands such as XMLHttpRequest could block the main thread until they were completed:

var request = new XMLHttpRequest();

request.open('GET', '/bar/foo.txt', false);

request.send(null); // Can take several seconds

Synchronous XMLHttpRequest has been deprecated because of the poor user experience but even some newer APIs like localstorage which access disk storage are synchronous. On a spinning platter disk this can take up to 10ms which is most of our frame budget.

Synchronous APIs simplified the way we write our scripts because the program’s state changed in the order the commands are written and nothing could happen in between until the previous command was completed.

Asynchronous APIs in the Web are needed for accessing computer resources which maybe a little slower such as reading from the disk, accessing the network or peripherals such as a web cam or a microphone. These APIs frequently relied on events or callbacks to handle these resources once they were ready.

// The deprecated way of using getUserMedia with callbacks:

function successCallback () {}

navigator.getUserMedia(*constraints*, *successCallback*, *errorCallback*);

// Using events for XMLHttpRequest

// via MDN WebDocs

function reqListener () {}

var oReq = new XMLHttpRequest();

oReq.addEventListener("load", reqListener);

oReq.open("GET", "http://www.example.org/example.txt");

oReq.send();

Node.js, a server side JavaScript environment, uses a lot of asynchronous code because Node needs to run efficiently on servers it can’t waste millions of CPU cycles waiting for IO operations to complete synchronously. Node often uses the callback pattern for asynchronous operations.

fs.readFile('/etc/passwd', (error, data) => {

if (error) throw error;

console.log(data);

});

Whilst callbacks are very useful unfortunately they create some code smells caused by nested asynchronous functions relying on the results of previous asynchronous functions this lead to code being very deeply indented known as the “callback pyramid of doom”.

To address this issues it became more common for newer APIs to use neither callbacks nor events but to use Promises instead. Promises use a .then syntax to make callbacks look a lot more readable:

fetch('/data.json')

**.then**(response => response.json())

**.then**(data => {

console.log(data);

});

Promises are functionally identical to callbacks but are a lot more readable. Especially when combined with es2015 arrow functions to clearly express how each step in the promise transforms the output of the previous step.

The real benefit of promises though is that they were a stepping stone to enable new JavaScript syntax introduced in EcmaScript 2017, async/await syntax.

In an async function await statements will pause the execution of the function until the promise they are awaiting completion of completes or rejects. The result is code which looks synchronous and can use synchronous constructs such as try/catch and for loops but behaves asynchronously without won’t block the main thread!

**async** function getData() {

const response = **await** fetch('data.json');

const data = **await** response.json();

console.log(data);

};

getData();

async functions will return a promise which itself can be used with await in other async functions it feels very elegant to me.

Lets talk about Web Workers

Everything we’ve talked about so far is for single threaded code. Even though asynchronous code looks like it happens at the same time it actually prevents execution of the rest of the website as each bit runs.

Usually each website runs on a single CPU thread for running JavaScript code, parsing CSS, and Layout and Painting the web site the user sees. JavaScript which takes a long time to run will stop anything else in the thread from running. If you prevent the website from being painted for too long this will give the user a really bad experience. In the past this could even crash the browser but they tend to be able to handle this better than in the past.

To get around the limits of running in a single thread the Web can make use of multiple threads on the Web through web workers, there are a few different types of workers for specialised applications such as service workers and worklets but we will be talking about the general purpose Web Workers.

You can start a new Web Worker running like so:

const worker = new Worker('/my-worker.js');

It will download the JavaScript file and run it in a different thread, this allows you to run complex JavaScript without blocking the main thread. In the example below we can compare the results of calculating 30000 digits of Pi on the main thread vs in a worker.

When it is done in the main thread the rest of the page is blocked, when it is done in the worker the page can keep running in the background until the calculation is completed.

To display the results of the worker the final Pi calculation has to be sent in a message to the main thread. The main thread then just handles displaying the number. The worker cannot display the number itself because it cannot access the variables of the main script or the document itself all it can do is pass back the final result of the calculations.

The reason for this is because of the nature of threads. You can only access things in the memory of the same thread. The document is in the main thread so the worker thread cannot do anything with it.

What even are threads?!

In the beginning computers were created. This has made a lot of people very angry and been widely regarded as a bad move. — Apologies to Douglas Adams

The following is a very simplified overview of how computers manage threads and memory.

In the early days of computers, computers could run one process at a time. Each program had access to CPU resources for doing calculations and Memory resources for storing information.

In the modern computation model programs still act as if this is still true even though many programs can run at the same time in parallel. Each process still uses one CPU and has access to the memory. This also prevents processes from writing into the memory of other processes.

The computer can run as many threads at the same time as it has computer cores, some Intel processors can run 2 threads per core.

The number of threads which can be present at the same time is disconnected from the physical reality of the CPU and memory because the computer can store multiple threads in memory and then switch between them. This is known as context switching it is an expensive operation since it involves clearing the CPUs L1-L3 caches and repopulating them from memory. Which can take around 100ns! This may still seem very fast but it’s 100s of CPU cycles spent idle so should be avoided whenever possible.

In addition the amount of memory programs can use is not tied to the memory that is physically present in the machine because the operating system will pretend to have almost limitless memory by using the hard drive for swap space, which is slower.

Using multiple threads wherever possible makes sense for modern hardware because Moores law no longer results in CPUs getting faster but instead the number of CPU cores on a single chip is increasing.

Whilst in traditional desktop/server computers each processor core is almost identical modern mobile chipsets frequently have processors of different power to increase battery life and stop the device over heating. Even though your may phone technically has a very powerful CPU in it, this may only run for short bursts to prevent it from getting too hot.

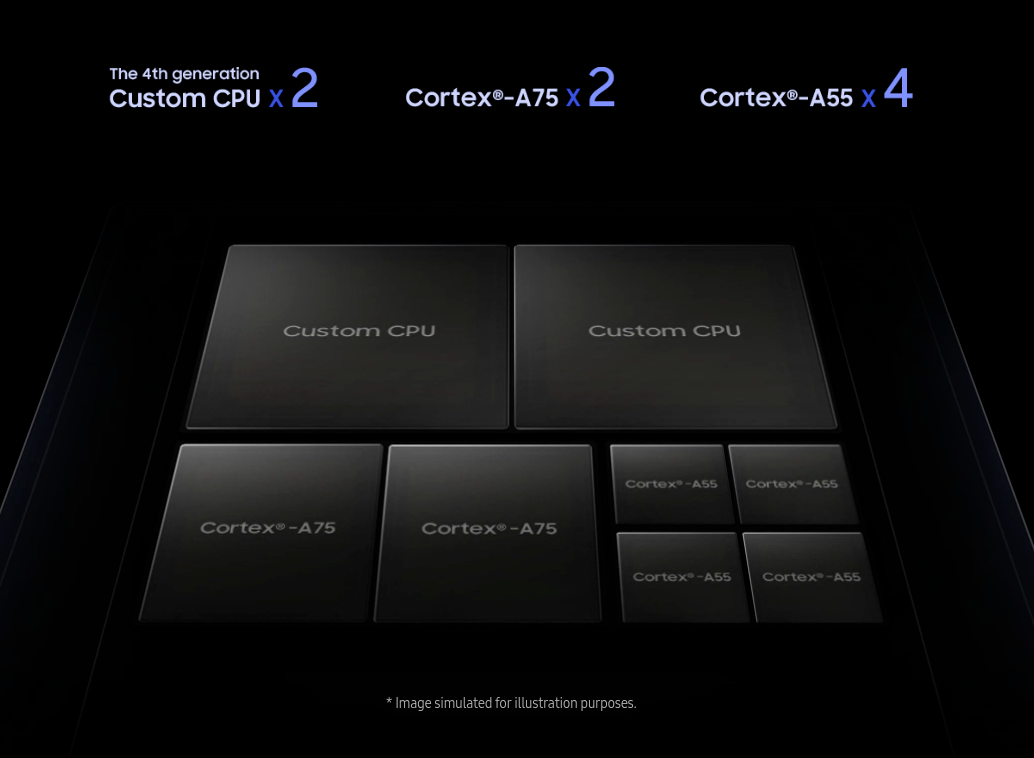

The Exynos 9820 in my phone as illustrated below has 2 big cores, 2 medium cores and 4 little cores.

Illustration of how processing power is split up on a mobile chipset.

Exynos 9 Series 9820 Processor: Specs, Features | Samsung Exynos

Samsung Exynos 9 Series 9820 is an LTE modem integrated octa-core mobile processor with tri-cluster that features 4th…www.samsung.com

Illustration of how processing power is split up on a mobile chipset.

Exynos 9 Series 9820 Processor: Specs, Features | Samsung Exynos

Samsung Exynos 9 Series 9820 is an LTE modem integrated octa-core mobile processor with tri-cluster that features 4th…www.samsung.com

Working around the limitations of threads

Although threads cannot share memory they can still talk to each other to exchange information. The API for this is event based, each thread listens for message events and can send messages using the postMessage API.

As well as strings, many types of data constructs such as Arrays and Objects can also be shared using postMessage. Sending these will result in the browser making a copy of the data structure in a special serialised format and then rebuilding it in the other thread:

// In the worker:

self.postMessage(someObject);

// In the main thread:

worker.addEventListener('message', msg => console.log(msg.data));

In this situation the object someObject is cloned and turned into a transferable form, this process is known as serialising. This is then received in the main thread and turned in to a copy of the original object. This can potentially be an expensive operation, but it maybe necessary for maintaining a complex data-structure.

For transferring large pieces of data you can transfer a chunk of memory instead, objects which can be transferred this way are known as Transferables. The type of object you are most likely to transfer for sharing data purposes is an ArrayBuffer.

An ArrayBuffer is part of the typed arrays API. You can’t write to ArrayBuffers directly you need to use a typed Array to read and write from it. The typed Array translates JavaScript Numbers to the raw bits and bytes which get stored in the Array Buffer.

You can also create a new Typed Array with a defined size and it will allocate a new piece of memory to accommodate that size. This chunk of memory is represented by an underlying ArrayBuffer and exposed as .buffer this instance of ArrayBuffer can be transferred between threads to share the contents.

// In the worker:

const buffer = new ArrayBuffer(32); // 32 Bytes

>> ArrayBuffer { byteLength: 32 }

const array = new Float32Array(buffer);

>> Float32Array [ 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0 ]; // 4 Bytes per element, so 8 elements long.

array[0] = 1;

array[1] = 2;

array[2] = 3;

self.postMessage(array.buffer, [array.buffer]);

Be careful if you transfer an ArrayBuffer using postMessage. Once it is transferred it is no longer available in the original thread for reading or writing and will throw an error if it you try to use it.

ArrayBuffers are data agnostic they are only chunks of memory. They don’t care what kind of data is stored. So you can use a single ArrayBuffer to store lots of smaller pieces of data of different types.

So if you need the efficiency of using ArrayBuffers but also need to handle complex data structures then if you are careful you can use a single ArrayBuffer. I wrote an article about storing slightly more complex structures in ArrayBuffers it goes into detail about how you can store different types of numbers in a single ArrayBuffer.

You can send messages back and forth using postMessage and using events for the response. Unfortunately using this in the real world is rather troublesome since keeping track of which response corresponds to which message is difficult for non-trivial use cases.

Using workers can give us great performance improvements, in an ideal situation with threads running on different processors communicating between them is very efficient.

We can’t control on which physical processor the operating system chooses to run processes on, nor can we control what other applications the user may also be running. So there maybe situations where both the worker and the main thread run on the same physical processor which would require a context switch before execution can start in the worker. There may also be situations when the worker is not the highest priority process on that CPU core so the worker thread may keep getting put into memory whilst some other task does work.

Making Using Threads Developer Friendly

Fortunately Surma at Google worked on an amazing JS library to turn this messaging back and forth into a promise based asynchrnous API! It’s called Comlink it is extremely small but hides a lot of the complications in dealing with the messaging loop to workers.

In the example below we instantiate a class exposed from the worker as a new object. We then call some methods from it. In the original class these methods were entirely synchronous but because it takes time to message to the worker and back Comlink returns a promise instead.

Fortunately async/awaitsyntax allows us to write asynchronous code which looks synchronous so the code still looks very neat and synchronous.

import {wrap} from '/comlink/comlink.js';

// This web worker uses Comlink's expose to expose a function

const MyMathLibrary = wrap(new Worker('/mymath.js'));

async function main() {

const myMath = await new MyMathLibrary();

const result1 = await myMath.add(2,2);

const result2 = await myMath.add(3,7);

return await myMath.multiply(result1, result2);

}

Look out! By hiding the complexity of using workers it also hides the cost of sending the data back and forth as well! This short snippet of code in main involves 6 messages between the worker happening in serial, each one waits for the previous to finish before running the next one. Each time a message is sent data will have to be serialized and reconstructed and a context switch may be required before we can get a response.

In the ideal situation the other thread is already running on a different CPU core and waiting for some input in which case everything runs very efficiently. If the thread isn’t being actively worked on the CPU may have to restore it from memory which maybe slow. We can’t control when an operating system changes threads, but by blocking code execution until a some code executes in the other thread we could potentially wait 100s of nanoseconds until we get our response back.

Writing legible and code is always a good thing but we must be wary of performance impacts. One way we could improve this would be calculating result1 and result2 in parallel. This would be a performance improvement but the code no longer looks as simple.

// This web worker uses Comlink's expose to expose a function

const MyMathLibrary = proxy(new Worker('/mymath.js'));

async function main() {

const myMath = await new MyMathLibrary();

const [result1, result2] = await Promise.all(

[myMath.add(2,2), myMath.add(3,7)]

);

return await myMath.multiply(result1, result2);

}

Another significant performance improvement you can do with Comlink is to take advantage of Transferables such as ArrayBuffers rather than copying them. This is really great for performance but be careful because once they have been transferred they become unusable in the original thread.

If you are working with transferables try authoring your code so that they are out of scope once transferred to prevent you from accidentally trying to read from them again.

const data = [1,2,3,4];

await (function () {

const toSend = Int16Array.from(data);

return myMath.addArray(

Comlink.transfer(toSend.buffer, [toSend.buffer])

);

}());

The transfer function is used to wrap what you are sending whilst marking the bits which are transferable in the second argument Array. Above I am sending toSend.buffer and telling Comlink that it can be transferred rather than copied.

Remember to handle the buffer case in your worker:

addArray(array) {

array = array.constructor === ArrayBuffer ?

new Int16Array(array) :

array;

When optimising your Comlink code be careful to balance the performance with code legibility. These optimisations can give you 10s or 100s of nanosecond improvements which are unnoticeable to users unless many happen at once for example in a for loop which loops 100s of times. Over optimised code which is harder to read may lead you to introducing hard to diagnose bugs.

Converting an existing code base to take advantage of workers

One wonderful benefit of Comlink is that it allows a developer to conveniently use part of their app in a worker without making huge changes to the codebase.

The biggest change you would make are to turn synchronous functions into asynchronous ones which await any usage of the api exposed from the worker.

Unfortunately moving all your code into a worker isn’t a magic push button solution.

You may get a small improvement in your frame rate because more work is taken off the main thread but you may find the the actual work takes a lot longer to complete if there is a lot of messaging back and forth.

For Example…

I wrote a demo in which Verlet integration is combined with SVGs to create wobbly interfaces.

Verlet Integration is a simple Physics model based on points and constraints. Each frame I would need to do a new physics calculation for the moving parts.

My demo also used a complex SVG filter to make a nice effect on the DOM elements. This filter used a lot of CPU on the main thread.

It worked great until the app had many points to be calculated with Verlet Integration at which point the time it took to do the Verlet Integration physics and the time it took to render the SVG was longer than the duration of a single frame (16ms).

Naively I moved my Verlet Integration code in to a Web Worker and the code await each API call.

When I tested the app it was no longer janky and skipping frames but the time to do a single physics calculation was taking a lot longer and didn’t look right on the screen.

I used Chrome’s performance tab to measure what was using up the CPU but to my surprise the CPU was mostly idle! What was going on?!

The issue came from having to switch threads many times in for loops. When switching between threads computer the computer may need to take information from memory to populate it’s caches which is comparatively slow.

// slow [😭](https://emojipedia.org/loudly-crying-face/)

for (let i=0;i<100;i++) await point.doPhysics(i);

I only had a certain amount of time and optimising the code often made it more complex to read. It was important to focus my efforts on the pieces of code which ran the most frequently and had the biggest effect on the user experience.

This was the order I picked:

-

Loops in PointerMove events, (runs faster than 60fps)

-

Loops in Request Animation Frame (60fps)

-

Loops which block app start up to improve user experience

-

PointerMove Events

-

Request Animation Frame

Optimising APIs which use Comlink

The most important thing to do is to MEASURE EVERY CHANGE you don’t know if or how much you have fixed anything unless you measure! You may even make something worse unknowingly unless you measure.

The performance api is used to provide accurate timings so you can see how long some code takes to run.

performance.clearMarks('start-doing-thing');

performance.clearMarks('end-doing-thing');

performance.clearMeasures("Time to do things");

performance.mark('start-doing-thing');

for (let i=0;i<100;i++) await myMath.doThing(i);

performance.mark('end-doing-thing');

performance.measure("Time to do things", 'start-doing-thing', 'end-doing-thing');

Once you have measured the code you want to optimise and ensured that it is indeed the cause of your performance issue it is time to start optimising it. Here are some ways you can do optimise a piece of code:

-

Delete it, do you really need it in the first place?

-

Cache it, will old data do? (May introduce unexpected errors.)

-

Make calculations run in parallel (this is okay):

arrayOfPromises = []; for (let i=0;i<100;i++) arrayOfPromises[i] = myMath.doThing(i); const results = await Promise.all(arrayOfPromises);

-

Change your API to handle receiving batches of inputs (this is better):

arrayOfArguments = []; for (let i=0;i<100;i++) arrayOfArguments[i] = i; const results = await myMath.doManyThings(arrayOfArguments);

If you do change your API to handle batches of input. Sending and returning an ArrayBuffer will make it even more efficient since the results or the arguments themselves may be a very large numeric Array.

Remember! Be careful when transferring Transferables between threads because they will become unusable once they are in the other thread.

Most Importantly

Writing code to run asynchronously across two threads is hard. There will be unexpected bugs because your code will run in parallel and things will not happen in the order you expect.

It is important to balance the developer experience and performance of the app. Don’t over-optimise code which has no impact on the end user.

In the below example the first version is a lot neater and easier for developers to understand and not too much slower then the bottom example.

const handle = await teapot.handle();

const spout = await teapot.spout();

const lid = await teapot.lid();

vs

const [handle, spout, lid] = await Promise.all([

teapot.handle(), teapot.spout(), teapot.lid()

]);

Optimise only in situations where the performance matters such as loops, rapid firing events like scroll or mousemove or in request animation frame.

Measure before you optimise, make sure you are not just wasting time optimising something the user will not notice. An extra 200ms before the app starts will probably go unnoticed. An extra 2000ms will probably drive away users, measure and test your performance.

Optimising too early may introduce unexpected bugs because the code is harder to read.

Even though writing asynchronous code is hard it can really pay off, it’s not suitable for every situation but occasionally it can be used to give your apps an incredibly smooth experience. It is not an essential feature but another tool in a web performance toolbox.

PostScript: Some interesting notes on performance.

The most important step when thinking about performance is working out where you bottlenecks are and measuring performance. The table below is a handy guide for thinking about where some of these costs come from.

This very rough guide to the timings of different types of IO operation will come in handy as I talk about fitting work into the tight budget of a single frame at 60 frames per second.

+---------------------------------------+-----------+

| Type | Time/ns |

+---------------------------------------+-----------+

| One frame at 60fps (16ms) | 16000000 |

| Accessing the disk (spinning platter) | 10000000 |

| Accessing the disk (solid state) | 150000 |

| Accessing memory | 100 |

| Accessing L3 cpu cache | 28 |

| Accessing L2 cpu cache | 3 |

| Accessing L1 cpu cache | 1 |

| 1 CPU cycle | 0.5 |

+---------------------------------------+-----------+ [**Computer Latency at a Human Scale** *How fast are computer systems really? Those of us who work in technology can blithely rattle off the clock speeds of…*www.prowesscorp.com](https://www.prowesscorp.com/computer-latency-at-a-human-scale/)

Interestingly 1 nanolightsecond is about 30cm, so during about a single 0.5s cpu cycle a signal can only travel about 15cm, approximately the length of a mobile telephone.

— Thanks to Surma and Daniel Appelquist for your feedback.

By undefined on May 13, 2019.